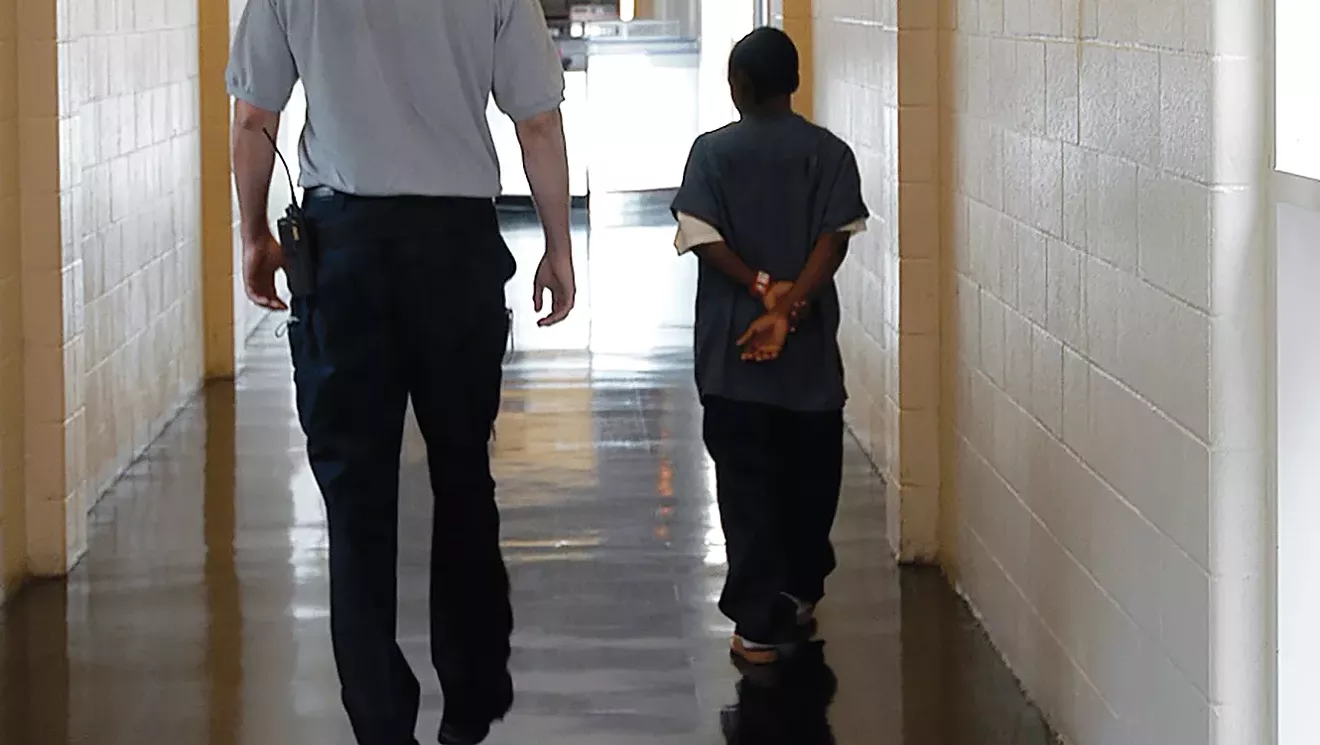

Credit: Glenn R. McGloughlin/Shutterstock

“We led the world in forward-thinking justice reform at one point, and we can do it again.” – Betsy Clarke, founder of the Juvenile Justice Initiative

Inspired by reform efforts in Ireland and Germany, Illinois activists are working to pass legislation that would offer more rehabilitation opportunities for youth offenders, allowing them to get their lives back on track and stay out of prison.

Senate Bill 2156, which has passed the Senate and moved to the House, is the first step by bill sponsor Sen. Rachel Ventura, D-Joliet, to improve Illinois’ juvenile justice system.

The bill would create a child reform task force, which would be tasked with gathering data statewide to gauge the effectiveness of the state’s juvenile correction centers. In addition, the task force would be charged with offering rehabilitative, community-based alternatives to juvenile detention.

Ventura said she was inspired to sponsor the bill after meeting with Ireland’s ministers of justice and law enforcement officials. She saw the differences in attitude toward repeated incarceration. Ventura said repeat offenders in the United States are viewed as the problem, while in Ireland, officials see repeat offenders as a failure of the system to properly address why someone continues to act out.

“I think part of this is a shift of understanding what we’re expecting children to do, especially children who maybe don’t have the means, versus what we’re expecting society and families to do,” said Ventura. “People will argue, no, that person needs to be punished and that somehow is a deterrent. I think there’s evidence that shows that’s not always the case. But at the same time, … this is about treating a child and what are the expectations of the child.”

Readjusting how the justice system approaches improving the lives of at-risk or incarcerated youth is a major factor for Ventura’s drive for reform. Another factor is acknowledging the lapses in the ability of Illinois correctional facilities to meet state and federal standards, due to understaffing and overcrowding.

With only 16 juvenile facilities across the state, some children are being sent hundreds of miles away from home to understaffed and overcrowded facilities unable to properly care for and rehabilitate them.

“There will probably need to be an appropriation to set up a new [program] that looks at how we’re streamlining these facilities, and training for officers and agents of the court, so we understand what the best practices look like,” said Ventura. “Some communities want control of their county facilities, and some don’t want the state to do anything with them. However, some of the 16 juvenile facilities across the state aren’t adhering to federal standards or to state standards.”

Ventura said inmate standards violations at some of the facilities include a lack of clean water, nutritional food and inadequate staff that leads to children being relegated to extended confinement without human interaction.

Betsy Clarke, founder of the Juvenile Justice Initiative, accompanied Ventura on her trips to Ireland and Germany to explore their justice systems. Her organization has worked since the early 2000s to raise the upper age of juvenile court jurisdiction from 17 to 18 and reduce the use of pretrial detention for young children.

Clarke says the least expensive alternatives are often the most effective. She also cites Illinois’ history as a world leader in juvenile justice reform, with the first separate court for youth founded here in 1899.

“We led the world in forward-thinking justice reform at one point, and we can do it again,” said Clarke.

Ventura and Clarke believe that rather than punishing children for acting out, addressing the root of a their problems and helping them better themselves will lead to fewer re-offenders, less strain on understaffed facilities and, ultimately, savings for taxpayers.

“I think people are starting to say if we’re going to lock people up, we need to be providing better services for them. So when they are released, and the majority of individuals do come home to their communities, they can integrate back into those communities and have a fighting chance at improving their life,” said Clarke.

Logan Bricker is a master’s degree student in the UIS Public Affairs Reporting program working this semester as an intern for Illinois Times.