Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks, which falls this year on

Monday, June 2, originated in biblical times as an agricultural festival, the

culmination of the spring grain harvest, which began around the time of

Passover with the reaping of barley and concluded with the gathering of wheat.

It was also the commencement of the season during which farmers brought the

first fruits of the harvest to the Temple, offerings from the crops considered

native to the land – the aforementioned grains as well as olives, figs, dates,

grapes and pomegranates. The holiday was one of three annual pilgrimage

festivals when people traveled to the Temple in Jerusalem to worship, to bring

offerings and to celebrate. Unlike the other festivals mentioned in the Torah,

the timing of Shavuot was not expressly linked to a particular month and day

but was determined by the counting of seven weeks following the beginning of

Passover.

In post-biblical times, the focus of Shavuot changed

from gratitude for the gifts of the harvest to the celebration of the giving of

the Torah at Mount Sinai. The identification of Shavuot with the revelation of

the Torah was facilitated by the opening verse of Chapter 19 of Exodus

mentioning that the Israelites arrived at Sinai at the beginning of the third

month following their departure from Egypt. I can only speculate on the reasons

for the shift in the holiday’s meaning – perhaps, the growth of a sizeable

Jewish population living in the Diaspora, a change in the occupational profile

of Jews (fewer farmers, more craftsmen and tradespeople), or the centrality of

the concept of Torah in the theology of the rabbis. Kibbutzim in Israel

used to (and may still) stage pageants at Shavuot time to emulate the biblical

festival of First Fruits and recapture its spirit. The book of Ruth, one of the

scriptural readings for the holiday, has an agricultural theme. Its central

figure, Ruth, is a widow and foreigner, who, during harvest time, provides for

herself and her mother-in-law Naomi, by gleaning in the fields of the wealthy

landowner Boaz, the kinsman of her late husband. However, the main scriptural

reading of the day is the Torah’s account of the Covenant and Revelation at

Sinai, and the holiday is now preeminently, as the liturgy refers to it, z’man

matan Torateinu, “the time of the giving of our Torah.”

The word Torah has a wide and diverse range of meanings, the

most common of which is to denote the Five Books of Moses, the first section of

the Hebrew scripture. While torah in a narrow sense can refer to a

specific set of laws – e.g., “this is the torah of the burnt offering,”

calling the Torah in its entirety “the Law” is a misnomer. The Five Books of

Moses contain chapters of narrative, poetry, and exhortation and constitute

much more than a statement and elaboration of law. A more proper and

etymologically sound translation would be teaching. Torah also has a wider

application and can mean the entire body of Jewish spiritual and religious

literature that has been written and handed down over the centuries and that is

derived from and rooted in the scriptures. To fulfill the commandments of the

Torah through our actions is a religious obligation; for an observant Jew it is

also obligatory to set aside time on a regular basis to study the Torah as a

source of guidance and inspiration. Every morning, we pray, “instill in our

hearts the desire to understand and discern, to listen, learn and teach, to

observe, perform and fulfill all the teachings of your Torah in love.” (The

Koren Siddur, translation by Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks)

Torah is regarded in Judaism as an expression of God’s love

and as a path to experiencing God’s presence in our lives. The giving of Torah

at Sinai is the fitting complement to the liberation of the Israelite slaves

which occurred but a few short weeks before and which we celebrate during

Passover. Freedom cannot be allowed to degenerate into anarchy or license. Our

personal freedom does not entitle us to exploit or oppress, to trample on the

dignity and well-being of our fellows, or to be indifferent to their suffering.

We need the framework provided by Torah to regulate our freedom, or as the

wordplay of the rabbis expressed it, true cherut (freedom) is attained

only by virtue of what is charut (incised) on the tablets of the

commandments.

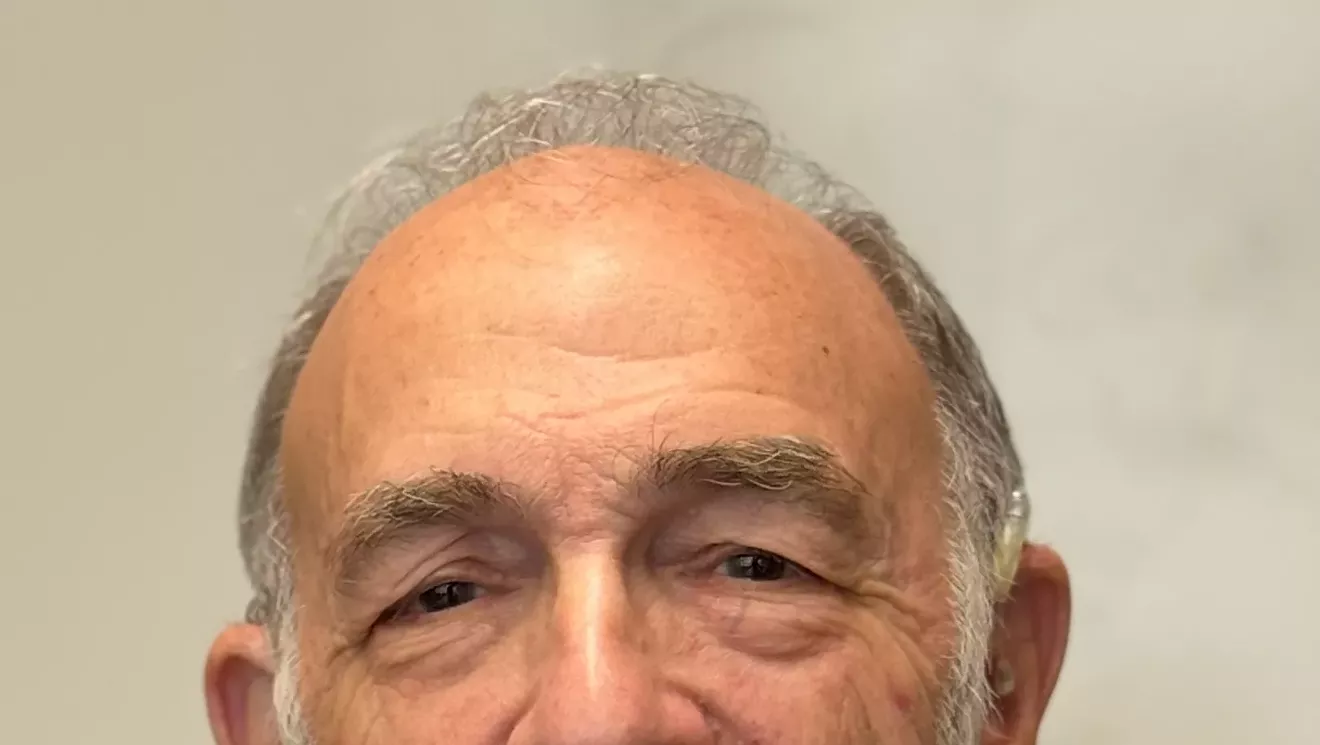

Rabbi Barry Marks is rabbi emeritus of Temple Israel in

Springfield.